Consul is a powerful tool for building effective distributed systems, and lately Clojure has been my language of choice for applications. Getting them to play well together is easy thanks to two libraries by Anatoly Polinsky, aka @tolitius. This post will cover the bare minimum to get Clojure, Consul, Mount, and Envoy to work well together.

While Consul has many usages, we’re going to be using Consul’s ability to serve as a distributed key-value store to share state or update configuration between distributed instances of the same application. One of the frustrations of testing out infrastructure tools is that they need an application to demonstrate their concepts. In this example, we’ll be using a dummy application called consul-printer, which won’t do anything except print messages based on Consul. You can find the finished source for the application, including Consul integration, here.

To start, we’ll run lein new app consul-printer and end up with some basic scaffolding. In project.clj, we’ll add a few dependencies and plugins.

:dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.8.0"]

[mount "0.1.11-SNAPSHOT"]

[tolitius/envoy "0.0.1-SNAPSHOT"]

[clj-time "0.12.2"]

[jarohen/chime "0.1.9"]

[environ "1.1.0"]]

:plugins [[lein-environ "1.1.0"]]

We’ll be using mount for mounting components and managing the internal state of the Clojure application, envoy for interacting with Consul, clj-time and chime for periodically printing messages, and environ for pulling environment variables.

Our main file, like many mount based applications, will just contain references to our components and a call to mount/start.

(ns consul-printer.core

(:require [mount.core :as mount]

[consul-printer.printer :refer [timer]])

(:gen-class))

(defn -main

[& args]

(mount/start)

Our printer namespace will initially have only one state, timer. This timer should periodically print a phrase when started, and cancel itself when stopped.

(ns consul-printer.printer

(:require [mount.core :as mount :refer [defstate]]

[envoy.core :as envoy]

[clj-time.core :as t]

[chime :refer [chime-at]]

[clj-time.periodic :refer [periodic-seq]]

[environ.core :refer [env]]))

(def config

{:printer {:interval 1000

:phrase "Test"}})

(defn periodic-print

[interval phrase]

(chime-at (periodic-seq (t/now) (-> interval t/millis))

(fn [time]

(println (str time) phrase))))

(defstate timer

:start (let [{:keys [interval phrase]} (:printer config)]

{:interval interval

:phrase phrase

:running? true

:cancel-fn (periodic-print interval phrase)})

:stop (do

((:cancel-fn timer))

{:running? false}))

Here periodic-print takes advantage of the chime/chime-at function, which can take an infinite sequence and a function, calling that function at each time in the infinite sequence. Our timer pulls from the config variable to configure what we print, and how often we print it.

This is the basic application we’ll be adding Consul functionality to, so now it’s time to set up the dev environment. A straightforward docker-compose.yml file will be used to bring up Consul:

version: "2"

services:

consul:

image: consul:0.7.1

ports:

- "8500:8500"

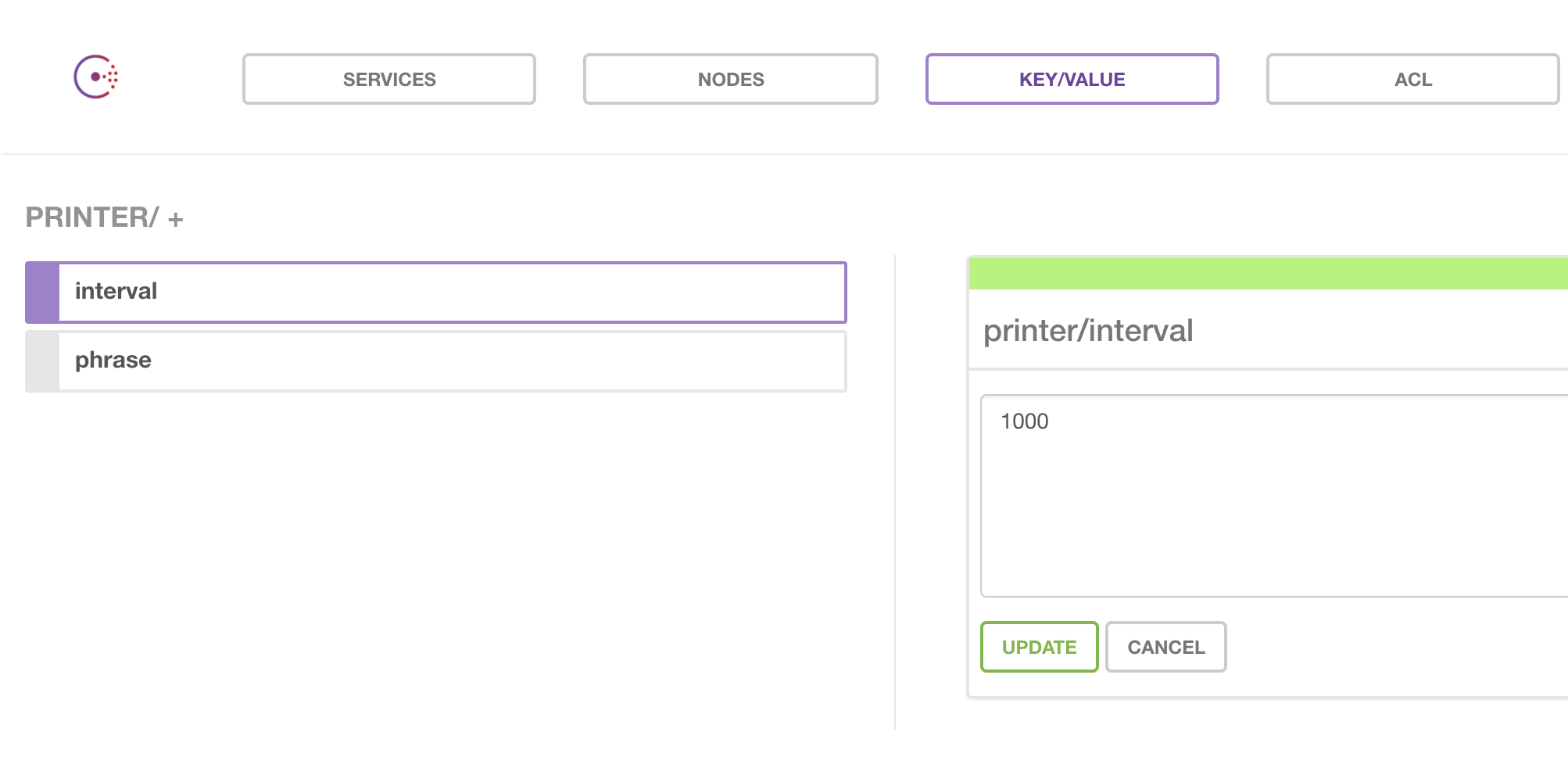

Running docker-compose up consul from the project directory will bring up a working instance of Consul. From the web app, we can add the printer/interval and printer/phrase keys like so:

Now, to point our Clojure app to Consul, we add a profiles.clj file containing the Consul API URL.

{:dev {:env {:consul-url "http://localhost:8500/v1/kv"}}

:test {:env {:consul-url "http://localhost:8500/v1/kv"}}}

At this point, we should start modifying our app to read from Consul. Anytime we introduce dependencies on outside databases in Clojure, we want to wrap that interaction in a state. Furthermore, instead of a hardcoded Clojure map, we’d like to read from Consul and make a map from that. To do that, we’ll be using envoy/consul->map, which takes a Consul URL and returns a nested Clojure map of the values, and replacing the previously defined config.

(defstate config

:start (envoy/consul->map (env :consul-url)))

If you already had a REPL running, you will need to restart it to properly pull the changes you made to profiles.clj. Running mount/start, we see that the program behaves exactly the same as before. We can update the values in Consul, and refresh them in our app using mount/stop followed by mount/start.

We’d like it if updating Consul automatically restarted our Mount components, though.

(def listener

(let [restart-vec [#'consul-printer.printer/config #'consul-printer.printer/timer]

watchers {:printer/interval restart-vec

:printer/phrase restart-vec}]

(mount/restart-listener watchers)))

(defn watch-consul [path]

(envoy/watch-path path #(mount/on-change listener (keys %))))

(defstate consul-watcher :start (watch-consul (str (config :consul) "/printer"))

:stop (envoy/stop consul-watcher))

Here we’re using a few important functions: mount/restart-listener, mount/on-change, and envoy/watch-path. To better understand what’s happening, let’s work from the inside out.

mount/restart-listener takes a map, and returns a listener that implements mount’s ChangeListener protocol. Each map entry has a keyword that represents the message being passed to your application to trigger a restart, and a vector of the components to restart.

We use that listener with the function mount/on-change. mount/on-change takes a listener and a collection of keywords, and if the collection of keywords matches any in the listener, actually triggers a restart of the corresponding components.

Finally, envoy/watch-path takes a path, in this case something like http://localhost:8500/v1/kv/printer. Everytime a key on that path is added or changed, or the value of that key is updated, it calls the corresponding function with the relevant changes. In this case we’re calling on-change, looking only at keys of the map that was passed, to see if we should trigger a config refresh.

Surprisingly, that’s it. An entire working example of Clojure and Consul, all in a file less than 40 lines long. Many thanks to Anatoly’s presentation at SoftwareGR that demonstrated these concepts, as well as his example project Hubble which demonstrates the same concepts in a larger application.